Leonard Hart’s Letter from Passchendaele

19 OCTOBER 1917

Letter from Leonard Hart to his family describing Passchendaele

France Oct 19, 1917 Dear Mother, Father and Connie, In a postcard which I sent you about a fortnight ago, I mentioned that we were on the eve of a great event, and that I had no time to write you a long letter. Well that great event is over now, and by some strange act of fortune I have once again come through without a scratch. The great event mentioned consisted of a desperate attack by our Division against a ridge, strongly fortified and strongly held by the Germans, but the name of which I had better not mention. For the first time in our brief history as an army the New Zealanders failed in their objective with the most appalling slaughter I have ever seen. My Company went into action 180 strong and we came out thirty-two strong. Still, we have nothing to be ashamed of as our commander afterwards told us that no troops in the world could possibly have taken the position, but this is small comfort when one remembers the hundreds of lives that have been lost and nothing gained. I will give you an account of the battle as near as I can without mentioning any names or exasperating the censor (should he happen to open this) too much.

On a certain Wednesday evening our Brigade received orders to proceed to the firing line and relieve a Brigade of Tommies who had two nights previously advanced their positions a distance of two thousand yards and had held the captured ground against several counter attacks by the Huns. These Tommies had, however, failed to take their last objective and we knew before we left that we were going to be put over the top to try and take it. At dusk we started off from the town where we had been billeted for a few days, in full fighting order, to proceed to the front line. Our track led over five miles of newly conquered ground without lines of communication, roads, or anything but shell holes half full of water. The weather had for some days been wet and cold and the mud was in places up to the knees. We struggled on through this sea of mud for some hours, and everyone was feeling pretty well done. It was quite common for a man to get stuck in the mud and have to get three or four to drag him out. You can have no idea of the utter desolation caused by modern shell fire.

The ground we were traversing had all been deluged with our shells before being taken from the Germans, and for those five miles leading to our front line trench there was nothing but utter desolation, not a blade of grass, or tree, here and there a heap of bricks marking where a village or farmhouse had once stood, numerous ‘tanks’ stuck in the mud, and for the rest, just one shell hole touching another. The torn up condition of the ground made the mud ten times worse than it would otherwise have been. The only structures which had stood the bombardment in any way at all were the German machine gun emplacements. These emplacements are marvellous structures made of concrete with walls often ten feet thick and the concrete reinforced throughout with railway irons and steel bands and bars. There is room inside them for a large number of men but of course they vary in size. Many of these emplacements had been shattered to pieces in spite of their strength but others had withstood the bombardment.

The ground was strewn with the corpses of numerous Huns and Tommies. Dead horses and mules lay everywhere, yet no attempt had been made to bury any of them. Well, we at length arrived at our destination – the front line and relieved the worn out Tommies. They had not attempted to dig trenches but had simply held the line by occupying a long line of shell holes, two or three men to each hole. Many of them seemed too worn out to walk properly and I don’t know how some of them must have got on during their long tramp through the mud back to billets. Each of us had a shovel with him, so we set to work to make some kind of trenches. We were at this point about half way up one slope of the ridge which in the course of forty-eight hours we were to try and take. The mud was not so bad here owing to the water being able to run away into a swamp at the foot of the ridge. Anyway by daybreak we had dug ourselves in sufficiently and, although wet and covered in mud from head to foot, we felt fit for a feed of bread and bully beef, for breakfast. We stayed in our new trenches all that day and the day following during which it rained off and on, and Fritz kept things lively with his artillery.

At 3 o’clock on the third morning we received orders to attack the ridge at half past five, which was just before daylight. We were accordingly arranged in three successive waves or lines; each wave about fifty yards ahead of the other. There was a certain amount of difficulty in this operation as it was pitch dark and raining heavily. When all was ready we were told to lay down and wait the order to charge. My Company was in the first wave of the attack which partly accounted for our heavy casualties. Our artillery barrage (curtain of fire) was to open out at twenty past five and play on the German positions on top of the ridge 150 yards ahead of us. It was to move forward fifty yards in every four minutes – that is to say we were to advance as our barrage advanced and keep 100 to 150 yards behind it. At twenty past five to the second, and with a roar that shook the ground, some three thousand of our guns opened out on the five mile sector of the advance. (The whole advance was on a five mile front and our Brigade occupied about a thousand yards of this front forming the centre of the advance.

Our Rifle Brigade was on our left and a Tommy Division on the left of them again. An Australian Division was on our right and another Tommy Division on the right of them again.) Through some blunder our artillery barrage opened up about two hundred yards short of the specified range and thus opened right in the midst of us. It was a truly awful time – our own men getting cut to pieces in dozens by our own guns. Immediate disorganisation followed. I heard an officer shout an order to the men to retire a short distance and wait for our barrage to lift. Some, who heard the order, did so. Others, not knowing what to do under the circumstances, stayed where they were, while others advanced towards the German positions, only to be mown down by his deadly rifle and machine gun fire. At length our barrage lifted and we all once more formed up and made a rush for the ridge. What was our dismay upon reaching almost to the top of the ridge to find a long line of practically undamaged German concrete machine gun emplacements with barbed wire entanglements in front of them fully fifty yards deep.

The wire had been cut in a few places by our artillery but only sufficient to allow a few men through it at a time. Even then what was left of us made an attempt to get through the wire and a fewactually penetrated as far as his emplacements only to be shot down as fast as they appeared. Dozens got hung up in the wire and shot down before their surviving comrades’ eyes. It was now broad daylight and what was left of us realised that the day was lost. We accordingly lay down in shell holes or any cover we could get and waited. Any man who showed his head was immediately shot. They were marvellous shots those Huns. We had lost nearly eighty per cent of our strength and gained about 300 yards of ground in the attempt. This 300 yards was useless to us for the Germans still held and dominated the ridge. We hung on all that day and night. There was no one to give us orders, all our officers of the Battalion having been killed or wounded with the exception of three, and these were all Second Lieutenants who could not give a definite order about the position without authority. All my Company officers were killed outright one of them the son of the Reverend Ryburn of Invercargill, was shot dead beside me.

The second day after this tragic business, we were surprised to see about half a dozen Huns suddenly appear waving a white flag. They proved to be Red Cross men and the flag was a sign that they were asking for a truce to take in their wounded and bury their dead. It was granted and not a shot was fired on either side during the whole of that afternoon. It was a humane and gallant act and one worthy of such gallant defenders as those particular Huns certainly were. Our stretcher bearers were able to go and take all our wounded from the barbed wire, a thing that would have been impossible otherwise. Numbers of us who at ordinary times had nothing to do with stretcher bearing were put on and we had all the wounded carried out before nightfall. We had no time to bury many of our dead but the wounded should be the only consideration at times like that. I went out and buried poor Ryburn. He came with the Main Body, but had not been in France long. The proportion of killed to wounded was exceptionally high compared to other battles, owing to the perfect marksmanship of the German machine gunners and snipers.

My Company has come out with no officers, only one Sergeant out of seven, one Corporal and thirty men. Even then we are not the worst off. The third night after the advance we were relieved and taken back about three miles behind the line. Here we acted as a reserve to the Battalion which had taken over our sector for two days, and we were finally taken right out to billets well behind the line where we are now recuperating. The night we came out here I received a parcel from you. The note inside was dated 10/7/17, and I can tell you that I felt hungry enough to eat note and all. I received another parcel from you about three days before we shifted to this front which would be about three weeks ago. They were appreciated about as well as it is possible to appreciate anything, I can assure you. Your letters of Mamma’s 25/7/17, Connie’s of same date and Dad’s of 7/7/17 arrived about a week before the affair of the ridge.

A number of our chaps who came through have since been sent to hospital chiefly with trench feet due to standing in cold mud for long hours. I have a touch of them myself but they are not bad enough to be sent away with. I have just decided to have this letter posted by someone going on leave to England, so I will tell you a few more facts which it would not have been advisable to mention otherwise...... Fighting of a very successful nature had been going on around Ypres for some months previous to our late set back at the ridge where the British are now held up. I hear that another attempt is to be made to take it, but it will not be with our Division. The name of this famous ridge is Passchendaele Ridge, and it has defied two attempts to take it already – viz the one attempted by the Tommies whom we relieved and our own......

The results of our stunt you now know so no more need be said about it except that we did as well or even better that some of the Divisions on our right and left. None of them took their objectives and I know for a fact that our Third Brigade’s losses and those of the Australians were every bit as heavy as ours. The Second Brigade has at least the satisfaction of knowing that they held a few hundred yards of ground they took, and our commander has since told us that no troops in the world could possibly have taken the ridge under similar circumstances. Some ‘terrible blunder’ has been made. Someone is responsible for that barbed wire not having been broken up by our artillery. Someone is responsible for the opening of our barrage in the midst of us instead of 150 yards ahead of us. Someone else is responsible for those machine gun emplacements being left practically intact, but the papers will all report another glorious success, and no one except those who actually took part in it will know any different.

In conclusion I will relate to you another little incident or two which never reaches the press, or if it does it is ‘censored’ in order to deceive the public. This almost unbelievable but perfectly true incident is as follows. During the night after we had relieved the Tommies prior to our attack on the ridge we were surprised to hear agonised cries of ’stretcher bearer’, ‘help’, ‘For God’s sake come here’ etc, coming from all sides of us. When daylight came some of us, myself included, crawled out to some adjacent shell holes from where the cries were coming and were astonished to find about half a dozen Tommies, badly wounded, some insane, others almost dead with starvation and exposure, lying stuck in the mud and too weak to move. We asked one man who seemed a little better than the rest what was the meaning of it and he said that if we cared to crawl about the shell holes all round about him we would find dozens more in similar plight. We were dumbfounded, but the awful truth remained. These chaps, wounded in the defence of their country, had been callously left to die the most awful of deaths in the half frozen mud while tens of thousands of able bodied men were camped within five miles of them behind the lines. All these Tommies (they were mostly men of the York and Lancaster Regiment) had been wounded during their unsuccessful attack on the ridge which we afterwards tried to take and at the time when we came upon them they must have been lying where they fell in the mud and rain for four days and nights. Those that were still alive had subsisted on the rations and water that they had carried with them or else had taken it from dead comrades beside them.

I have seen some pretty rotten sights during the two and half years of active service, but I must say that this fairly sickened me. We crawled back to our trenches and inside of an hour all our stretcher bearers were working like the heroes that they were, and in full view of the enemy who, to his credit, did not fire on them. They worked all day carrying out those Tommies of whom I am afraid some will be mad men for the rest of their lives even if they do recover from their wounds and exposure. Carrying wounded over such country often knee deep in mud is the most trying work imaginable, and I do not say for a moment that the exhausted Tommies (the survivors of the first attack on Passchendale Ridge) whom we relieved should have tried to carry them out for I do not believe that any of them were physically capable of doing it, but I do say that it was part of their officers’ duty to send back to the rear of the lines and have fresh men brought up to carry out the wounded that they themselves could not carry. Perhaps they did send back for help, but still the fact remains that nothing was done until our chaps came up, and whoever is responsible for the unnecessary sacrifice of those lives deserves to be shot more than any Hun ever did. If they had asked for an armistice to carry out their wounded I do not doubt that it would have been granted for the Huns had plenty of wounded to attend to as well as the Tommies. I suppose our armchair leaders call this British stubbornness. If this represents British stubbornness then it is time we called it by a new name. I would suggest callous brutality as a substitute. Apparently this is not an isolated instance of its kind.

While we were in reserve for two days to the Brigade which finally took over from us I was having a look around some old German dugouts and in one of them I came upon about fifty dead Tommies all lying spread out over the floor as though they had been thrown in there hastily. They had evidently been dead some months. I asked an artillery Sergeant Major standing nearby how they all came to be in there and he told me that they had been put in there (while wounded) during the advance last July, and had been forgotten. If this were true then it is even worse than the case just mentioned, for these dugouts must have been within a mile of our main dressing stations at the time when the advance took place, and the distance to carry them was thus five times less than in the other case. After reading this do not believe our lying press, who tell you that all the brutality of this war is on the Huns’ side. The Hun is no angel, we all know, and the granting of an armistice such as that which we had is a rare occurrence. The particular Regiments who were holding the ridge at the time our attack are known as ‘Jaegers’. Probably the Prussians or most of the other Hun Regiments do not ask for armistices, but for all the terrific casualties those Jaegers inflicted on us, we survivors of Passchendaele Ridge must all admit that they played the game on that occasion at any rate...... I remain Your affectionate son Len.

MS-Papers-2157-5

‘Someone is responsible…’

The Alexander Turnbull Library holds a substantial collection of original documents on the subject of World War I, including the letters of Leonard and Adrian Hart.

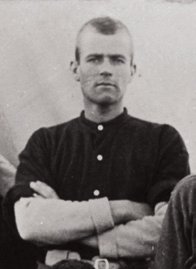

Leonard Hart served in the Otago Infantry Battalion and the Second Brigade in the Middle East and France. Adrian was a farrier with the New Zealand Field Engineers.

Leonard’s letters to his parents on Somes Island, where his father was the lighthouse keeper, display a keen intelligence and critical eye in their recording of the events going on around him. Nowhere is this more evident than in the polemic of his letter home, written just a week after the disastrous involvement of the New Zealand Division at Passchendaele on 12 October 1917.

Leonard and his letters both survived the war. Leonard eventually returned to his career with the railways, and his letters and those of Adrian came to the Library in the 1980s. They form part of the manuscripts collection in the series MS-Papers-2157-1-7.